Acknowledgements: Thank you to all the individuals who were involved in this project. A special thank you to the Indigenous women who participated whilst they were completing their sentences, or awaiting sentencing, at Établissement de Détention Leclerc de Laval. We could not have done this without your trusting and courageous contributions. Thank you to Établissement de Détention Leclerc de Laval, the provincial prison we partnered with to carry out the research project. Thank you to all the community organizations involved in the project including Quebec Native Women, La Société Elizabeth Fry du Québec, Chez Doris, Portage, The Native Women’s Shelter of Montreal, and Native Para-Judicial Services of Quebec.

The rate at which Indigenous women are incarcerated is disproportionately and alarmingly high. While Indigenous women represent less than 5% of the Canadian female population, they represented almost half (48%) of female admissions to custody in 2021 (Statistics Canada, 2016, 2019; Correctional Investigator of Canada (CIC), 2021). Indigenous women consistently fall through the gaps of a system that has proven itself to be harmful towards them. There is an urgent need to better understand and educate about the experiences and circumstances of Indigenous women. We must better support Indigenous women’s healing and rehabilitation in the context of criminalisation and incarceration and develop strategies to decrease the rates of incarceration and recidivism.

This report summarises a research project that began in 2018 with the intention of exploring how to better support the healing of Indigenous women navigating the criminal justice system. The research addresses the disproportionate representation of Indigenous women incarcerated in Canada, and more specifically in the province of Quebec. The research project was comprised of three major components. The first was a Master’s project conducted by Brittany Weisgarber (2020) exploring the impact of mainstream and culturally specific programs for Indigenous women’s healing in a Quebec women’s provincial prison: Établissement de Détention Leclerc de Laval (herein called the Leclerc Detention Centre in Laval). Weisgarber explored the experiences and perspectives of Indigenous women who were provincially incarcerated through workshops and interviews. Following these workshops and interviews, our research team interviewed prison staff at Leclerc Detention Centre in Laval and individuals working in community organizations in Tio'tià:ke, Montreal that support Indigenous women navigating the prison and justice system. This report is a culmination of all three components. The research provides a holistic lens to understanding the realities, barriers and hopes for Indigenous women’s healing in the context of the criminal justice system, specifically within the provincial setting of Quebec. The aim of this report is to share our findings and offer some recommendations and insights that can be applied to various contexts, in order to inform our collective actions and responsibility to do better at supporting the healing of Indigenous women who are navigating the prison system.

This report has been designed to engage you, the reader, in reflection and learning alongside us. We will be asking prompting questions throughout as an invitation for personal reflection. Our findings and recommendations are not ‘one size fits all’, they must be adapted and applied to the realities of your organization and/or community.

The over-incarceration of Indigenous people is currently a Human Rights crisis in Canada. The CIC (2017) states that the “over-incarceration of First Nations, Métis and Inuit people in corrections is among the most pressing social-justice and human-rights issues in Canada today” (p. 46). This issue particularly impacts Indigenous women. For decades, Indigenous female offenders have been treated as triple-deviants— ostracized for their race, cultural norms, traditions, and beliefs, in addition to not fulfilling their gender-normative role expectations such as caregiving (Monture-Angus, 2000). Statistics demonstrate the disproportionate impact on Indigenous women:

In order to address the over-incarceration of Indigenous women, we must talk about the systemic factors that led us to where we are today: The impacts of colonization, colonial genocide, intergenerational trauma, loss of cultural identity, and lateral violence. The legacy of colonization has a direct link to the over-incarceration of Indigenous women. Therefore, it is important that we begin by contextualising the research within these systemic realities.

In order to colonize and settle on Indigenous lands, European settlers put in systemic processes to disenfranchise and disconnect Indigenous people from one another and from their ancestral lands. Settlers imposed laws, policies, and practices that forced Indigenous peoples to give up their traditions and ways of being. Strategies included forcibly seizing land, uprooting communities, restricting movement of Indigenous peoples, banning languages, persecuting spiritual leaders, forbidding spiritual practices, confiscating spiritual objects, and significantly disrupting and separating families (e.g., residential schools). These practices contributed to the genocide of Indigenous people (Truth and Reconciliation of Canada (TRC), 2015). The impacts of these actions and colonization have contributed to the over-incarceration of Indigenous people today. There is a huge need for a collective reframing and re-imagining of our current reality that shifts blame and responsibility for change away from Indigenous people and instead holds the systems, policies, laws, discourses, and structures responsible for upholding a culture of colonization (Monchalin, 2016).

Colonial genocide was a structural and systemic strategy used to destroy Indigenous people and dismantle Indigenous cultural identity, which was recognized in our study as an important element of Indigenous strength and resilience (Yuen & Pedlar, 1999). Colonial genocide is a slow-moving process. The policies of colonial destruction of Indigenous peoples took place insidiously and over decades. The acts of violence and intent to destroy are structural, systemic, and cut across multiple administrations and governments (National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, 2019). A significant form of colonial genocide and the destruction of Indigenous cultural identity was through the residential school system: Children were forcibly removed from their families and traditional lands, disconnected from the spiritual practices, banned from speaking their Native languages; punished for doing so, and forbidden to use any reminders of their home and their culture (Baskin, 2016; TRC, 2015). In addition, children were subjected to neglect, physical abuse, sexual abuse, loneliness, disease, racism, and discrimination (Barnes & Josefowitz, 2018). Those who survived were not allowed to return home to their communities. These experiences affected survivors’ social, emotional, and relational development. The impacts of this abuse are being felt today through the cycle of intergenerational trauma. Furthermore, prisons have been argued to be extensions of residential schools (Sugar & Fox, 1990) and the reserve system, which governs and controls Indigenous lands and spaces (Struthers & Moore, 2018).

When a group of people have been subjected to traumas over a long period of time, the following generations continue to be impacted long after the original traumatic events occurred. High rates of mental health challenges, disease, substance abuse, under-education, under-employment, and other forms of abuse are manifestations of intergenerational trauma (Desjarlais, 2012; National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, 2019). Indigenous women in prison recognize these traumas as deep scars (Yuen & Pedlar, 2009), while others describe it as a soul-wound (Duran & Duran, 1995). Colonization, systemic racism, and the lack of education about these systems, which are built on Eurocentric values and ideologies, continue to contribute to systemic oppression of Indigenous peoples today and their disproportionate interaction with systems of criminal justice, such as the police and prisons. This systemic oppression continues the cycle of intergenerational trauma amongst Indigenous communities.

This term is defined by Native Women’s Association of Canada (NWAC, n.d.) as “when a powerful oppressor has directed oppression against a group for a period of time, members of the oppressed group feel powerless to fight back and they eventually turn their anger against each other” (p.1). Colonization, systemic racism, and the lack of education about the impacts of these forms of structural oppression in school curriculums contribute to the prevalent negative narratives about Indigenous peoples in Canadian society. These narratives can be internalised by individuals who are Indigenous and can result in violence and abuse within Indigenous communities.

Indigenous cultures value women as sacred life bearers and often use a matrilineal structure in their communities. The imposition of patriarchal laws and policies, resulting from colonization, stripped women of their power, status, freedoms, and resources. This oppression directly impacts Indigenous women’s amplified experiences of violence and incarceration today. Indigenous women experience higher rates of poverty, under-education, under-employment, sexual and physical abuse, survival sex work, coercive sex, violence, trauma, and criminalisation, all of which have been linked to colonization (Oliver et al., 2015; McGregor, 2018; National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, 2019). The incessant exposure to oppression and abuse has contributed to Indigenous women’s pathways to crime and their over-incarceration.

Despite the Canadian government’s recognition of the systemic barriers that negatively impact Indigenous people’s healing, incarceration rates of Indigenous women are going up. Correctional Service Canada has established healing lodges, integrated Elders and Indigenous liaison workers, and increased cultural competency training for prison staff in federal prisons. These actions are in response to the government’s recognition of the systemic barriers Indigenous people face resulting in over-criminalization and over-incarceration. However, their attempts to reduce incarceration rates for Indigenous peoples have been ineffective. Indigenous scholars have stated that this is because it is not possible to heal harms caused by colonization using colonial solutions (Hewitt, 2016). The Viens Commission (2019) highlighted the presence and impact of systemic racism within the justice system. There is a tendency for the prison system to take on a pan-Indigenous approach, which assumes the rich and diverse Indigenous cultures that exist are homogenous, and therefore does not attend to the real needs of the diverse Indigenous populations in prisons. Moreover, the limited resources which are available are designed for Indigenous men or non-Indigenous women (Vecchio, 2018; Wesley, 2012). For example, Waseskun Healing Center offers holistic healing programs for criminalized Indigenous men.

Consequently, programs and services that are available do not meet the needs of Indigenous women and have the potential to be harmful (Viens Commission). Our research indicates that there is a significant gap in the available programs for Indigenous women in a provincial prison context.

We sought to explore and better understand the healing and rehabilitation experiences and needs of Indigenous women in Quebec prisons. Therefore, we partnered with a Quebec provincial prison, Leclerc Detention Centre in Laval, and held 31 in-depth interviews and five three-day workshops, engaging a total of 38 incarcerated Indigenous women. We also held one-to-one interviews with 11 middle management and staff at Leclerc Detention Centre in Laval to understand their perceptions of Indigenous women and their needs, and their understandings of rehabilitation and colonization. Lastly, we interviewed 16 individuals working in the community and supporting Indigenous women who are navigating the criminal justice system.

The women that participated in the study are a diverse group from various cultural backgrounds. The women’s ages were between 20 and 56 years and represented a range of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities: Inuit (20), Algonquian (4), Cree (3), Mi’kmaw (1), Métis (1), Inuk/Cree (1), Algonquian,/Cree/Montagnais (1). In terms of languages spoken, 11 women were trilingual and spoke their Indigenous language, French, and English fluently; 18 were bilingual and spoke their Indigenous language and either French or English; one spoke only French, and one spoke only English. The women’s first languages included Inuktitut (21); French (4); English (2); Cree (1); Cree and English (1); and Algonquian and English (1). This range of identities and language proficiency demonstrates the need for an approach that recognises and honours the diversity that exists within Indigenous cultures. The diversity of languages also highlights a clear need for resources to be accessible in various languages. Of the women who participated, 25 had children and two were pregnant at the time of their involvement in the study. The women’s time in prison further separated them from their families and communities. Their sentences ranged from 10 days to 469 days, and some were awaiting sentencing. Only four women were in prison for the first time, while 27 had been previously incarcerated at the provincial level and none had been federally incarcerated. These numbers illustrate the rate of return to prison (including breach of conditions of parole and recidivism), which will be discussed in more detail in this report. Throughout the report, references to ‘the women’ and ‘Indigenous women’ refers to Indigenous women who were, at the time of the research, incarcerated in Leclerc Detention Centre in Laval, and participated in the workshops and interviews. The names of the women have been changed to ensure their confidentiality.

We interviewed representatives from different units of the prison, probation officers, pastoral staff, and correctional officers/guards. Two of the staff joined in the past year whilst all the rest have worked there for five years or more. When asked to identify their race, two of the staff indicated they had mixed racial backgrounds and all others described themselves as white, Canadian, or Québécois. They described having many responsibilities as part of their role, which at times resulted in feeling overwhelmed or unable to adequately respond to the needs of the individuals in the prison. Members of staff from Leclerc Detention Centre in Laval who were interviewed are referred to as ‘prison staff’ in the report and their names have been changed to protect their confidentiality.

We interviewed 16 individuals who work in the community, representing the following organizations: Elizabeth Fry du Québec, Chez Doris, Iskwe Project, Portage, Native Women’s Shelter of Montreal, Native Para-Judicial Services of Quebec, and McGill University. Almost half (44%) of the people we spoke to are Indigenous and were able to apply their lived experience combined with their professional experiences to offer perspectives that helped shape the recommendations offered in this report. We noticed the synergy between what was shared by the women who were incarcerated and the Indigenous individuals working to support them in the community. This connection demonstrates the importance of including and centring Indigenous voices and perspectives when developing services for Indigenous communities. It is as important to recognise the diversity of Indigenous cultures and adapt resources to fit the groups that are represented in our communities. Of the Indigenous community workers we spoke to; two were Cree, one was Cree/Métis, two were Mohawk, one was Inuk/French Canadian, and one was Huron-Wendat/Québécoise. Of the 16 individuals we spoke to, seven worked in the community for less than 10 years, four worked in the community for 10 to 20 years, and two worked in the community for 20 to 30 years. Throughout the report, these Individuals, who are working in community organizations that support Indigenous women in the criminal justice system, are referred to as either their positions within their organizations, ‘community workers’, or ‘individuals working in the community’. With permission and as directed, we have identified the names and organizations of some community workers.

We used a decolonizing approach that invited a more holistic, relational, and flexible lens. Decolonizing means going forward by looking back, recognizing, and documenting colonial relations, and advocating for and striving for change (Smith, 1999; Tuhiwai-Smith, 1999). Moreover, decolonization looks like deconstructing and unlearning normative concepts of governance and justice, by considering ways of knowing that centre wellbeing, rather than colonial control (Grande, 2015). Historically, research has harmed Indigenous communities rather than benefitted them as it has often been used to justify racist and culturally inappropriate policies and practices (Kovach, 2009; Mihesuah, 1998; Tuhiwai Smith, 1999). Therefore, there is an understandable distrust in engaging in research initiatives amongst Indigenous communities. We believe the recognition of the academic sector’s contribution to colonization and harm of Indigenous peoples is an important consideration for any project involving Indigenous peoples.

We addressed this issue by emphasizing collaboration and relational practices, ethical processes, and rooting research in Indigenous knowledges. Our approach was influenced by the Ownership Control Access Possession (OCAP) principles, Chapter 9 of the Tri-Council Policy Statement, and the research protocols of the Assembly of First Nations of Quebec and Labrador. On-going discussion and transparency with the women who participated in the study and the team, regarding the Indigenous women’s ownership, control, and possession of the data collected, was critical to our process (OCAP: First Nations Centre, 2007).

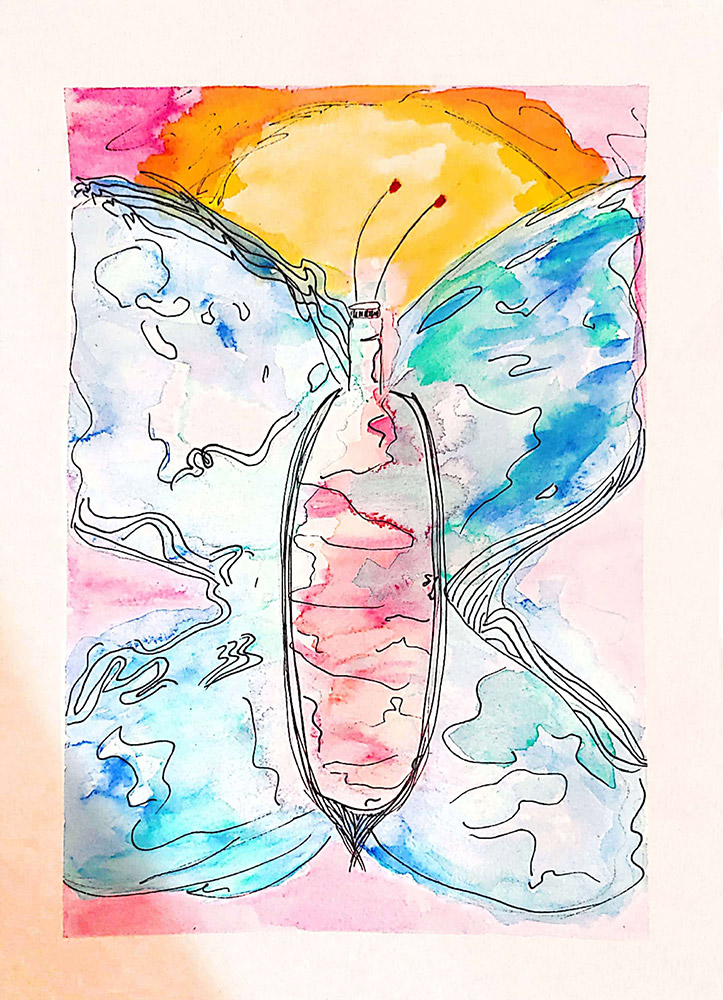

Our intention in data collection was to move beyond Eurocentric ways of knowing and towards Indigenous ways of knowing. Data was collected through a blended approach of one-to-one interviews and arts-based methods during the workshops. The workshops were fluid in that they did not follow a strict structure but instead were shaped by the Healer and/or Elder facilitating as well as the needs, cultures and preferences of the women present. During the workshops, the women and the research team members present collectively engaged in traditional ceremonies and practices such as feasting, smudging, drumming, sharing circles, and the making of medicine pouches1. Arts-based methods give space for experiences and emotions to be recognized, identified, and addressed, and create opportunities to develop new ways of thinking and knowing (Bolt, 2019; Myre, 2021).

1See image of a medicine pouch made by one of the women during the workshops. A medicine pouch is a sacred item, made from leather, that is usually used to carry Indigenous medicines or a special token that is significant or sacred to the person.

To respect the ceremonial nature of the workshops, we captured the learnings visually in 16 Sketchnotes2 (Rohde, 2013) that the women were able to interact with (e.g., change, add, erase) and ultimately obtain control over the way they were being represented. A woman asked to take home the Sketchnote from the workshop, and so we shifted our plan to create a copy for each woman. This process further encouraged the principle of reciprocity and ownership over the data by the women, which resulted in further sharing of the learnings amongst the women’s communities. Moreover, other Indigenous women in the prison wanted to get involved in the research after seeing the Sketchnotes.

2See image of a Sketchnote created by Brittany Weisgarber from the first day of the second workshop series.

We made further changes to the initial plan, based on a relational approach which incorporated advice and knowledge shared by the women and the learning and experiences of the research team. Our facilitators were Indigenous Elders and Healers. Wanda Gabriel, who is Mohawk, and Vicky Boldo, who is Cree/Coast Salish, facilitated the first few workshops. Many of the women were Inuit and the facilitators received feedback from the women that having Inuit workers involved in the process would make it more relatable and comfortable for them. As a result, Nina Segalowitz, who is Inuk/Dene, joined the team. She contributed to the research team’s understanding and knowledge of Inuit ways of being and was able to apply this to the workshops, making them safer and culturally meaningful for Inuit women. This process reinforced the diversity that exists amongst Indigenous cultures and the need to move away from a pan-Indigenous approach. The women also requested that the workshops lasted more than three days because the final days felt rushed. Therefore, the fourth and fifth workshops went on for an extra half day, with the support of the prison.

Each workshop looked different, whilst still sharing the same content, depending on the preferences of the women present. Facilitators used different approaches to discuss important themes and theories. For example, one described trauma with the story of ‘the onion,’ where healing looks like peeling back the layers of trauma. Whilst another described it as ‘internal barbed wire,’ that would be unravelled through healing3. These messages reflected the facilitators’ own different experiences and perspectives, whilst still delivering the same content, in their own way. These adaptations demonstrated the importance of flexibility and reciprocity in the process of healing for Indigenous women. The research team listened, learned, and responded to the women in order to better suit the process to their needs. The aim was to root the experience in Indigenous knowledge and demonstrate the value of doing so. This process, in turn, also supported building trusting relationships between the women and the facilitators.

3The images of the onion and barbed wire are depicted in the Sketchnote.

There were also some changes in the prison itself as a result of the women’s feedback. Many women expressed a desire for historically accurate and culturally relevant library books. This need was expressed through a newspaper article and collective action led by two individuals. A few Indigenous community organizations responded with a large donation of such books for the prison library. Women also voiced a need for resources such as pens, paper, notebooks, and the names and contact information for community resources and organizations. The research team created packages, provided by Quebec Native Women, that included a notebook, a pen, wellness cards, a journal, a book on Indigenous sexuality, a blanket, and a lunchbox. Quebec Native Women and Elizabeth Fry du Québec also prepared resource booklets and phone numbers of organizations that could support the women. However, the women shared that calling cards were expensive at the prison and so packages were coordinated so the women could call these services free of charge.

Knowledge and access to these resources had lasting impacts on several of the women. Victoria, an Inuk woman who participated in the workshops, used the resource booklet to find information about applying to finish two thirds of her sentence in a community setting and ended up finding a halfway house where she could complete her sentence. By using the resource booklets, Lori-Ann, an Algonquin woman, who attended the workshops was able to contact the First Nations Education Council who helped her complete courses that contributed to her high school diploma. She could not have taken these courses at the prison itself, as they were not available in English4.

4The images of the onion and barbed wire are depicted in the Sketchnote.

Data collection and analysis was also flexible and relational. Each researcher took their own approach to collecting and analysing the data. Brittany Weisgarber drew Sketchnotes during each workshop with the women and then later reflected and re-drew each Sketchnote to highlight the themes based on conversations the women expressed as most important. During data analysis, Brittany engaged in a Sketchnotes drawing process that integrated themes from the workshop with messages that the women shared in their interviews. In analysing the prison staff data, Pamela Gabriel-Ferland drew from her own Indigenous knowledge, as well as her Western academic training, to identify patterns, gaps, and connections to systemic issues. Rowena Tam analysed the data from community organizations by drawing on her background in creative arts therapies. She reflected on each interview through sketchbook drawings, immersing herself in the illustration, replaying powerful vignettes and sinking deeper into the presence of each story. Furthermore, Pamela and Rowena have connections and relationships within the Indigenous communities and organizations in Tio'tia:ke, Montreal. These connections supported their understanding and processes in relation to the analysis, rooting it in Indigenous knowledge. Rowena expressed how the research project supported her reciprocal learning as she identified new connections and opportunities for collaboration.

Here are some key learnings and considerations that arose as we moved through and adapted the process:

These are important elements to consider for all interventions and initiatives designed to support Indigenous women and communities.

There is an urgent need for change in the healing and rehabilitative experiences of Indigenous women navigating the criminal justice system. The change is necessary to reduce the number of Indigenous women in prison and increase culturally relevant systems of support for criminalized Indigenous women. The research highlighted the cycle of systemic harm that impacts Indigenous women in the criminal justice system disproportionately. We heard across the three groups (Indigenous women, prison staff, and community workers) that we must begin by examining colonization and its ongoing impacts on our communities. Indigenous communities have and continue to experience colonial genocide, intergenerational trauma, systemic racism, and over-incarceration. These are interlinked and maintained by colonial structures and processes that govern this country. These structures include the Department of Youth protection (DYP), federal and provincial prison systems, and the police system. To move towards the future we want, one that offers a decolonial approach to supporting our collective healing…

The legacy of colonization, colonial harm, intergenerational trauma, and systemic racism are not to be considered shortcomings of Indigenous communities or misidentified as the legacy of Indigenous peoples. Rather, these are forms of systemic oppression that have created the conditions for the barriers and difficulties that Indigenous women face today, including over-incarceration. Algonquin, Métis, Huron, and Scottish scholar Monchalin (2016) asserts that “over-representation should be framed as the “problem” of discourses, laws, and cultures in the territories of Indigenous peoples” (p. 363). Understanding and addressing colonization as the root of the problem at a collective and cultural level is the first step towards better supporting Indigenous women in prison and the wider Indigenous community more generally. The research illustrates the ongoing harm of colonization, including colonial genocide, intergenerational trauma, colonial structures that perpetuate systemic racism, and the resulting impacts on Indigenous women.

As you read through this section, we invite you to consider:

Colonization, colonial genocide, and the residential school system contributed to a loss of cultural knowledge and access to their languages and traditional practices. Many of the incarcerated women involved in the study were hopeful about passing on their culture, practices, languages, and traditions onto the future generations but the persistent removal of children from their families by DYP continues to disrupt the transmission of cultural knowledge. Bailey, a Cree woman incarcerated at Leclerc Detention Centre in Laval, shares her experience: “My little cousins, they’re in foster homes in different communities. My aunties’ kids, they speak French and English, they don’t know their Cree language. They all live in different places. They all got separated.” Squirley, who is Algonquin, expressed her desire for her children’s connection with their culture: “I want my grandkids to grow up knowing that, and not growing up like I did, not knowing my own language.” Serge, who supports Indigenous women’s transition back into the community after release, comments on the impact of this separation of Indigenous women from their families: “DYP is a big problem. We need more support there from the onset, because I think a lot of these women wouldn’t be in the positions they were in if they had their children with them.”

Connection to culture and community are an integral part of Indigenous healing and wellbeing and Elders play an important role in connecting Indigenous communities to their spiritual and cultural knowledge. Teachings from Elders provide guidance to the women, however, colonial structures and systems, such as residential schools, the DYP, and prison, have severed the connection between Indigenous children and Elders for generations. The women described a lack of spiritual practice and lack of culture as consequences of this rupture. The Elders hold deep wisdom and there is a fear that this will be lost. Nukilik, an Inuk woman at Leclerc Detention Centre in Laval, shares: “The Elders will pass away soon. I need to learn so I can teach my kids.” The systematic disruption and destruction of Indigenous cultures has a direct impact on their wellbeing, health, and safety. Wanda, a Mohawk facilitator and Elder working in the community, explains: “Because what genocide does is traumatic, and trauma disconnects us from self. So, healing is about reconnecting to self, finding balance, and looking at self in a holistic way.” This reconnection to self and community is an integral element of healing for Indigenous women and communities.

The trauma endured by Indigenous communities is passed down through generations. Due to the trauma residential school survivors experienced, they were sometimes unable to provide emotional warmth and care to their children. As a result, some of the women described their own childhood experiences of being in physical danger, being exposed to violence, and unsafe conditions in spaces that should feel safe. Bailey, who is Cree, shared, “When I was a kid I used to see a lot of violence at my place. They were always drinking and I was scared all the time.” Some women had their physical needs met, however their parents were unable to provide emotional care. Ayla, who is Inuk, illustrated such an experience: “My parents were there making sure I wasn’t hungry. But they weren’t there mentally.”

Many women were removed from their homes by DYP and described being passed around foster homes, group homes, rehabilitation centres, juvenile detention, and prison: “I was always in a foster home. And when I was 14, I ended up in the lock down unit, and they sent me to a group home. When I was 18, I went back and I started going to jail” (Jasmine, Cree). Some of the women expressed their experiences of abuse and harm in these settings: “I don’t like them [foster parents]. When I came out at the age of 13 telling her what he was doing to me, I got beaten. I call that a family from hell” (Squirley, Algonquin).

These experiences and the structure of the DYP resulted in many of the women having their children removed from their care, continuing the cycle of intergenerational trauma. The women described developing coping mechanisms to survive their circumstances and the trauma: “They took my baby away…I had her for six months, and then they placed her [in care], and that’s when everything started, all the drugs and alcohol use” (Iris, Algonquin). The separation between the women and their children affected their mental wellbeing and created anxieties and fears about losing their connections with their children: “I’m not happy. I’m worried my kids are going to forget me. This happened with my youngest baby when I went home in November. He didn’t remember me” (Nukilik, Inuk).

Valentina, a prison staff member, described how colonisation impacts Indigenous women: “When a People are broken, it’s for sure that this gets transmitted from generation to generation.” The support that is provided to Indigenous women in prison does not adequately address these circumstances. Sonya, who is Inuk and French Canadian and works in Native Para-Judicial Services of Quebec, described the limitations of not integrating an awareness of these realities into the services available for incarcerated Indigenous women:

The justice system, prison system, the education system, and the DYP are examples of colonial structures that continue to contribute towards harm in Indigenous communities. The erasure of the impact of colonization in Canada’s educational curricula has led to widespread racism against Indigenous peoples and lateral violence amongst Indigenous communities. Lori-Ann, an Algonquin woman in Leclerc, described her experience of racism in school and its impacts:

« The teacher has said I will never learn, and I will never amount to anything »

The women also experienced judgement from guards in the prison. For example, Fanny (Inuk) was told by a guard: “I know the problem is alcohol because you are Inuit… Inuit always drink.” Many of the women themselves also believed that alcoholism was the problem and by stopping drinking, their problems would be solved. These experiences and responses illustrate the lack of knowledge about colonization and its impacts.

A couple of the women described an incident of racist harm whereby the guards kept a group of Indigenous women out in the cold whilst it was -30 degrees. They had wanted to get some air and then the officers refused to let them back in for up to an hour saying, “Anyway, they're Inuit, and they're resistant to the cold.” Breana, a community case worker, shared stories she had heard from Indigenous women in prison: “They didn't necessarily feel safe as Indigenous people. They often talk about the racism that they've experienced, especially, while incarcerated.” Several community workers, who interacted and did work with prisons directly, described the lack of understanding, care, and support provided by the prison guards. Vicky, a Cree and Métis cultural support worker, shared stories she had heard from women in prison about the rate of negative interactions with prison guards and mistreatment that does not support the dignity of the women. Serge, a community worker, connected such processes to the training of prison guards, “For them, their job has never been to care for these people, so it's a whole different culture to accept that the incarcerated women can play a role into the management of the environment they live in.”

The systems that are set up to supposedly support Indigenous women’s rehabilitation often exclude and restrict them from being able to heal. Many members working in the community described prison as an inadequate environment for healing. Sonya, an Inuk/French Canadian community worker, shared the impact on Indigenous women specifically:

Activities that are offered to the women often reinforce colonial systems and structures. They are Eurocentric, and do not consider Indigenous cultural practices and traditions. Important Indigenous ceremonies have been banned in prisons as they were not deemed appropriate. Women, prison staff, and community workers alike emphasized the difficulties of receiving clearance from authorities to access sacred medicines, such as tobacco, sweet grass, and sage, and the matches needed to start the smudge. Restricting access to these items are an impediment to the healing of Indigenous women. The women shared the ways in which the available programs were culturally inappropriate and at times the women were court mandated to attend them. Furthermore, the funding structures of available programs are based on a Eurocentric model which determined the value of a program by the number of women who attended. This way of measuring impact has been referenced as a limitation to the advancements of Indigenous systems for justice and healing in Canadian correctional contexts (Hewitt, 2016; McMillan, 2016). There is a need to better understand and value Indigenous approaches to healing as valid and effective.

Individuals working in the community describe the Western architecture, structure, and environment of prison as a barrier to Indigenous women’s healing. Adherence to this dominant prison system results in a lack of culturally specific resources, access to nature, Elders, traditional practices, foods, cultural training for prison staff, and resources in English and Indigenous languages. This system also contributes to women’s experiences of discrimination, prejudice and racism, and a pervasive punitive culture. Anna, a Cree community worker, shares, “They have country food maybe once in a while, but I don't think no one's allowed to have their small, medicine bundle [often containing medicines such as tobacco and sage] with them and I don't think that a prison can be really culturally safer.”

The prison dynamics and processes are barriers to some women in engaging with programs designed to support their rehabilitation. For example, prison guards often act as gatekeepers to entering programs which can lead to some women staying on the waiting list far longer than others. This process paired with the lack of awareness prison staff have about Indigenous practices and the different cultures and Nations that exist, can result in Indigenous women being blocked from accessing helpful services. Simone (Algonquin) shared, “[Guard] told me that I’m not Inuit so that’s why they don’t call me to go [to the activity]. Actually, I almost cried because I couldn’t go. I want to go.” The available programs at the prison were designed for Inuit. There was also a lack of clarity about whether First Nations women could attend the programs and at times this created tension amongst Indigenous women. Lori-Ann, who is also Algonquin, shared her experience, “The Free Inuksuk I am glad I stepped in the room anyway. They are kind of racist, you know? Some accept me, some don’t.” This experience illustrates how colonial conditions and lack of awareness from those in power can contribute to tensions amongst Indigenous communities and lateral violence.

Furthermore, prison programs are designed in cumulative sessions, which makes them confusing or repetitive for some of the women as often they would have to join halfway through the program depending on the timing of their sentence5. The program design also meant that women who were in the prison for longer or returned to prison had to repeat programs and their learning became stagnant. “They gave me a certificate, but it stops at 10. [Lesson]1-10… the same thing, I want something [new] to learn” (Tapeesa, Inuk). The women also expressed the need to have space to connect with one another more often as the culturally specific programs took place for only a few hours a week and they were often placed in different units. The women shared that their culture is part of their everyday lives and they wished to be able to have daily gatherings in order to connect and feel a sense of comfort and safety.

5The average stay for women in Quebec provincial prison is 45 days.

Women also shared how services and programs would get cut during the summer due to low staff availability. “Our visitations and our gym is cut during the summer because there’s no guard there at night” (Lori-Ann, Algonquin). Some community workers also described how they were not allowed access to the prison during certain times, which blocked the women’s access to services and programs, particularly those that were culturally appropriate. Anna, a Cree community worker, shared her experience during a workshop for Indigenous people in the prison: “she [guard] decided to put on hold our workshop and to bring that in the…crystal tower to make decisions about who we are and if we can come again. We had to be really strategic.” This approach was echoed by other community workers who described that they must be careful and strategic just to gain entry into the prison and provide more culturally specific support.

Several of the prison staff described their admiration for Indigenous women for their resilience in the face of suffering. Julie described Indigenous women as “people who are intelligent, capable, that have lived a lot in their lives, and continue to persevere.” There was an understanding of the difficulties that Indigenous women face, however many did not identify the impact of colonization as the root issue but rather focused on the symptoms such as alcoholism and violence. Prison staff recognised their lack of education about Indigenous culture and the history of colonization. Sam shared, “I don’t know enough, and want to know more. I try to learn, but I don’t fully understand why they are on land reserved for Natives, why, and since when?” Prison staff described first learning about negative stereotypes and tropes about Indigenous peoples in their childhood and in school. They shared the ways in which their perspectives shifted after working with Indigenous populations in the prison system and informed themselves out of personal interest. Vanessa described how she began learning about Indigenous cultures, “I started to become interested…you know, with all we have heard about the history of colonization, and assimilation, I felt compelled to do something.” She also emphasized learning from the band and community partners. Many prison staff were able to describe the negative impacts colonization has had on Indigenous communities. Importantly, several expressed a need to learn more and identified training for staff as an important way that the prison environment could better support Indigenous women. Charlotte shared, “I’ve been screaming this since I started: Staff need training.” Cristine shared how she learned a lot from speaking with Elders and community partners: “I really learned with the partners and speaking with Elders who come here. They have a real desire to teach us.”

« I’ve been screaming this since I started: Staff need training »

I am feeling unsure about what to do. Today some of the Inuit women in the prison asked me to do a workshop where we make dream catchers. But dream catchers are not traditionally part of Inuit culture. They originate from the Anishinaabe peoples. Who am I to hold a workshop like that when I am not Indigenous myself? I feel deep discomfort as I want to support and listen to the women’s needs, however I do not want to contribute to cultural appropriation7. It makes me realise just how important it is to educate ourselves, as support workers and practitioners, on the nuances of systemic racism and the different realities of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis cultures. This awareness and education is foundational if we are to challenge the misuse and exploitation of different cultural traditions and practices. Why is it so difficult for us non-Indigenous folks in Quebec to move beyond our current ways of being and thinking? How can we encompass a wider range of perspectives that can help us challenge systemic racism and better support the Indigenous women who are suffering within the prison system? I have been taught to avoid this discomfort that I feel. But I made a commitment to let myself feel the discomfort and take the time to really reckon with it. I know it will only help me become a better supporter for Indigenous women. We need to do more to recognise how our services might be culturally problematic and perpetuate the issues we are trying to resolve. Should I honour the Inuit women’s request? Is it my place? Could I find a practitioner who is Anishinaabe to deliver the workshops? This is why we need to work together.

6This story is adapted from an Interview with one of the community workers. The drawing was created by Rowena Tam as part of her data analysis.

7Cultural appropriation is the inappropriate adoption of an element or elements of one culture or identity by members of another culture or identity. This can be controversial when members of a dominant culture appropriate from minority cultures.

Take some time to journal after reading this story using the following prompts:

Our study indicates that the disconnection from Indigenous cultural identity, which first occurred through the history of colonization and residential schools, continues today through the criminal justice system. Participants emphasized cultural identity is a hugely important part of Indigenous communities’ strength and resilience. However, the lack of culturally appropriate languages and forms of communication that dominate the current justice and prison system create unfair barriers for Indigenous communities and can lead to their over-representation in prison. Sonya, an Inuk/French Canadian community worker, describes the ways that information will get lost in translation between the legal system and Indigenous peoples:

« The loss of language in between and the understanding, it's huge… The language barrier is huge »

Reinforcing the findings of the Viens Commission (2019), the conditions of probation also result in rates of recidivism and return to prison as they are not appropriate to Indigenous communities and their context. As described by the prison staff, breaching the conditions of parole is the most prevalent reason Indigenous women return to provincial prison. Prison staff emphasized that often the conditions imposed on the women cannot be realistically followed when they are released from prison due to the circumstances to which they are being released. As described by Madeleine, “It’s often the same people who come back from [Indigenous communities]. Up North, alcohol has a very strong presence.” Indeed for many, staying away from alcohol is a condition of parole, however it is difficult for them to do this in their communities. As noted by the Viens Commission, conditions of parole are not well adapted to Indigenous realities. Conditions of parole can also block the women from being able to access services that support them. Breana, who is a community case worker, shares:

« she was not allowed around the Cabot Square area. But, all her services, such as us – the people who come to court with her – are right outside Cabot Square »

Individuals working in the community described how women are released back to the place they committed the crime, rather than back to their homes and communities. This increases the risk of return to prison. Liane, who is setting up a transition house for women leaving rehab, shares the difficulties facing women as they transition back into society: “I got my sentence. Here's my release date. Okay, I'm leaving. Well, I'm going to go right back home. I'm going to have a drink, and I'm going to fight again, right?” She continues, “There has to be a bridge between being released and reintegrating.” For some women, their circumstances outside prison may be more dangerous. Jissika (Inuk), shared, “I need help to find my own apartment than living with a boyfriend, cause every time I live with the boyfriend, we end up arguing and I end up coming to prison…to have my own key and not be kicked out and end up living on the street.” The lack of resources available for Indigenous women whilst in prison to help them gain access to housing contributes to this cycle of harm. Natasha (Inuk) described her own concerns about re-integrating after forming a dependence on the structure of control and surveillance in prison: “I got used to being in jail, being controlled. What time we eat, what time we need medication, what time we go to activities. It was kind of scary for me… having to re-learn how to be outside myself.”

« There has to be a bridge between being released and reintegrating »

There is a need for more tailored resources based on the realities of the women after release, in order to reduce rates of return to prison. Some Indigenous communities have greater access to resources to support women with re-integration, whilst others have no access to help at all. This discrepancy highlights the need for better reporting processes that document the different Indigenous cultures and communities represented in prisons, and the need for continuous support beyond release to accompany Indigenous women. Prison staff who have more knowledge about the realities of the Indigenous communities that the women will return to are better equipped to support the women’s release and reduce rates of return to prison. Cristine, a prison staff member who spent time up North visiting three Inuit villages, as part of a program offered by a partner community organization, shared some insights into how to better support Indigenous women: “Working with communities to be able to adapt our release plans so the women can be able to rehabilitate. We don’t impose conditions that could be realistically followed in the community.”

« We don’t impose conditions that could be realistically followed in the community »

Women described strategies they used to cope with their traumatic experiences, such as blocking their emotions, using different methods such as drugs, alcohol, unsafe sex, fighting, and over-working. There was an acknowledgement that processing their experiences and emotions was part of healing, however blocking them was also sometimes needed as a way to survive:

For some, using drugs and alcohol was a tool to cope with their trauma. Elizabeth, who is Inuk, shared, “Just not to feel any bad things I had to drink.” The women also described how bottling up their emotions could lead to explosions. “I built up that wall a long time ago… when I explode, I used to be a dangerous woman” (Natasha, Inuk). For some, drugs and alcohol were used as a way to feel their emotions: “Don’t talk, don’t trust, don’t feel. I don’t know, it’s like I always used alcohol and drugs to be able to break it out” (Iris, Algonquin). However, releasing their emotions whilst intoxicated did not necessarily lead to healing. “When I end up getting drunk I start talking, crying, yelling. When I am sober, I come back and start all over again” (Jissika, Inuk). Jissika continued to share that, for some, prison was a place they could come to stay sober: “Before I came here I had a problem with drugs...Even my friends out there started telling me to go to prison to go take care of myself.”

Experiences of loneliness were described by many of the women. For some, it was a way to keep safe. Many had painful relationships with their families due to the legacy of colonization. Some were beaten by their parents. Some felt they could not talk to their parents or they had to raise themselves entirely. Iris (Algonquin) shared, “I have to try and be a parent to myself.” As some of the women grew up and became mothers themselves, they felt guilt and loneliness when the DYP forcibly took their children away from them. Kate (Inuk) shared her sorrows when her child was taken from her, “She thought I abandoned her. The social workers, the DYP workers, they have to teach kids who they take away from their parents. They have to say it’s our fault, not your mother’s. She feels abandoned.” These broken and difficult relationships caused some of the women to feel that they needed to be alone, and some turned to criminal activity as a way to feel needed. Lori-Ann (Algonquin) commented on this: “Because I was always like a loner, and alone, and well, you feel important right? People are calling you up: I need this, I want that.” Being in prison further contributed to feelings of loneliness as they were separated from their family, land, and communities: “It’s hard to be here… Because I’m Inuk here, I’m alone. I need to go be with Inuk people” (Mollie, Inuk).

« Because I’m Inuk here, I’m alone. I need to go be with Inuk people »

Indigenous practices and communities emphasise a holistic approach to healing, which involves connection and re-connection to cultural traditions, practices, spirituality, languages, and community. Relationships and continuity are integral in supporting Indigenous collective healing. It is important that we listen to Indigenous individuals and communities and apply their ways of being into our services and systems. We can all learn from Indigenous teachings in support of our collective healing towards the future we want: one that decreases the rate of incarceration of Indigenous women and supports their healing in a culturally relevant way.

As you read through this section, we invite you to consider:

Indigenous cultures teach us that all parts of life are interconnected. The Indigenous people working in the community to support incarcerated Indigenous women described healing as a holistic practice that restores balance between different components of one’s being such as family, community, self, mind, body, and spirit. Anna (Cree) gave context and meaning to the word, “Holistic is a cool word. It just means take care of the whole person with whatever they're coming with or their needs are. I think it needs people to create programs or projects to be really flexible… we come to meet up with the woman and then they can lead us.” Wanda (Mohawk) shares, “If we don't bring that [holistic approach] to the processes, we're continuing to colonize. Because colonization was pretty effective at destroying cultural pride [and] cultural expression. In order to be fully who we are, if you take a holistic perspective, culture [and] spirit [are] part of that.” Gabrielle, who is also Mohawk, talks about the ways in which colonization has severed the connections between all aspects of life, “It's a connection, it's a spirituality that's involved, and… they've lost track of that. It's spirituality and their teachings, family connections, and [the] importance of being thankful, and the Creator. Everything that's involved holistically.” Véronique (Huron-Wendat/Québécoise) shared her doubts about the possibility of prison meeting this need for Indigenous women, but she believes that there are ways that they might improve:

« Holistic is a cool word. It just means take care of the whole person with whatever they're coming with or their needs are. I think it needs people to create programs or projects to be really flexible… we come to meet up with the woman and then they can lead us »

Colonial approaches and worldviews separate aspects of life, such as work life, family life, leisure, whereas Indigenous worldviews see all aspects of life as inherently connected (Little Bear, 2000). The women appreciated when the support they received used this holistic approach. For example, the use of the medicine wheel in workshops8. The medicine wheel can be used in different ways, depending on teachings from various Indigenous Nations. For our workshops, the four directions (East, South, West, North) represented a corresponding factor (physical, emotional, intellectual, spiritual) and moved clockwise from the East. The medicine wheel was used as a guide during activities and as a means for data analysis and representation for the research project. Collectively, the medicine wheel represents balance, harmony, and wholeness. Our analysis of culturally specific programs in the prison indicated that they included all four elements of the medicine wheel. That is, the workshops that were offered as part of the research to the women in prison had physical, emotional, intellectual and spiritual benefits. Whereas the mainstream programs that were offered by the prison only fit into a specific section. For example, the gym program had physical benefits and the art therapy sessions offered intellectual and emotional benefits, however their lack of spiritual specificity meant that they did not fit the holistic healing needs of Indigenous women. The colonial tendency to compartmentalise and separate impacts how even the culturally specific programs are made available. Each program is only available at the prison at certain times during the week for a few hours. This practice contradicts the ways Indigenous communities view these activities as integrated into their day to day rather than compartmentalised activities with set times.

8See image below of a Sketchnote created by Brittany Weisgarber, from day one of workshop four, that demonstrates the use of the medicine wheel.

The women described feeling shame about their culture, which has also been described by Indigenous women in federal prison (Yuen & Pedlar, 2009). These feelings of shame demonstrate the impact of colonization on disconnecting them from their cultural knowledge and pride, as well as the long-term experiences of systemic racism. Culturally specific programs give space for women to reconnect to their cultural and spiritual knowledge, traditions, and practices, as well as their languages. Such experiences build a sense of cultural pride, strength, positive self-esteem, confidence, and resilience, which supports positive Indigenous cultural identities (Beaudette, Power, & Ritchie, 2019; Desjarlais, 2021). These spaces allow for the women to release shame through traditional ceremony, such as smudging. Our project demonstrated that crafting, drumming, and singing supported the development of cultural pride amongst the women along with experiences of self-love, acceptance, and forgiveness. The women described how reconnecting with their culture and spirituality helped them to release their shame and forgive and accept themselves. Tapeesa (Inuk) shared the impact of engaging in cultural activities, “I’m learning how to love myself.” Simone (Algonquin) shared how traditional practices supported her mental health, sense of self-worth and pride, and kept her going despite her hardships:

« I’m learning how to love myself »

Jissika (Inuk) described the impact of eating traditional foods and engaging in cultural activities, “Eating my rabbit… it’s not just that. When we were doing our workshop, I wasn’t feeling like I was in prison… After that I was in my grandmother’s kitchen.” Culturally specific programs give the women opportunities to discover, rebuild, or renew their spirituality. “Being incarcerated for the first time actually tells me that I really, really need to pay attention to my cultural values” (Simone, Algonquin). Natasha (Inuk) further elaborated on the decolonial power of tradition: “It feels like refuel...our tradition. Cause when you are in jail, in Montreal, or in any kind of White people’s land it feels like we are losing.”

Wanda, a Mohawk facilitator and Elder in the community, describes the integral role of culture in improving the prison system, “I think the biggest barriers are discrimination, racism, ignorance, lack of understanding of how important culture is.” Indigenous individuals who are working in the community described how connection to culture creates a sense of belonging, safety, and pride. They shared the positive impact of culturally relevant practices for Indigenous women in prison such as speaking their languages, offering smudging, rewording questions so that they are better understood, being available to offer support, access to Elders, feasts, ceremonies, sharing circles, and arts and crafts, such as beading and making medicine pouches.

« I think the biggest barriers are discrimination, racism, ignorance, lack of understanding of how important culture is »

Importantly a diversity of cultures, traditions and languages exist amongst Indigenous communities. First Nations women described having different needs to Inuit women. Lori-Ann (Algonquin) shares her appreciation after participating in the workshops which integrated First Nations cultural practices, partly due to the facilitators who were a mix of Mohawk, Cree, Coast Salish, Métis, Inuk and Dene: “The country food was awesome. I wish we had more of that also. Like the Inuit, they get it every three or four months. But [not] the First Nations— the Algonquin and the Cree.” Sonya (Inuk/French-Canadian) who works in the community, also shared, “the Inuit get country food brought in but the First Nations don't have a thing. They don't have moose, they don't have deer, they don't have any kind of traditional packages coming into them. So, they feel very forgotten.”

« the Inuit get country food brought in but the First Nations don't have a thing. They don't have moose, they don't have deer, they don't have any kind of traditional packages coming into them »

Our study highlights the benefits of having spaces that invite diverse Indigenous communities to connect. Participants of the workshop recognized that cultures of other women present in the workshop may have been different from their own, but also valued each other’s knowledge and learned from each other to build collective strength, and ultimately filling gaps in cultural knowledge that were lost due to colonization. This being said, it is essential to recognise and provide culturally relevant support to the various Indigenous cultures that are represented in prisons. Prison staff expressed uncertainty about the number of Indigenous women in the prison. One stated that the numbers can be hard to calculate, and sometimes Indigenous people are not spotted. This lack of knowledge speaks to the ways in which Indigenous women may fall through the gaps without adequate structures and processes that support them, as well as a need to better identify the different distinct cultures represented in prisons in order to ensure that support is culturally relevant.

Women in the prison have been removed from their family, community, and their lands. As emphasized by the participants who are Indigenous in this study, Indigenous cultures value relationships and connections to their families, communities, lands, mind, body, and spirit as part of their healing. Strategies for addressing the root of harm through collective healing and Indigenous resilience, include connection to land and place, restoration of tradition, language, and spirituality, and privileging stories and storytelling (Oliver et al., 2015). In this project, sacred medicines, ceremony, crafting with traditional materials, singing, drumming, feasting on country food, sharing circles, and other cultural practices helped women to experience and maintain a spiritual connection to the land, their homes, families, and communities whilst in prison.

Programs that are inclusive to the diverse cultural backgrounds of Indigenous women, such as the medicine pouch workshop as part of this study, contributed to collective healing and building their collective strength through reciprocal sharing of their different cultural knowledge and practices. Recognizing tobacco, sage, and sweetgrass are medicines for many First Nations, and moss is medicine common to the region of Nunavik where Inuit live, facilitators made sure to bring all sacred medicines. Facilitators representing various Indigenous cultures were also deliberately invited to facilitate. This approach differs from the pan-Indigenous approach that Correctional Service Canada programs have been criticized for using (Waldram, 1997; Wellman, 2017; Combs, 2018).

Storytelling and sharing circles are a means of individual autonomy and healing as well as collective healing (Kovach, 2009; Gutierrez, Chadwick, & Wanamaker, 2018; Friedland, 2016). Our study identified several benefits of these processes including access to teachings and stories, collective remembrance of ancestral knowledge and ways of life, understanding the impacts of colonization, feeling represented in stories of others, sharing about self, and witnessing others healing. The women shared how learning about colonization helped them understand and have context for their challenges and supported their healing. Access to Elders and Healers and their teachings also supported Indigenous women’s healing. The women in the prison emphasized the importance of hearing the facilitators share their own personal stories and felt connected to and represented by the Elders and Healers who led the workshops. The women also appreciated hearing and relating to other women’s stories:

The structure of the sharing circle allowed the women to choose if they were ready to share or not. Some participants preferred to simply listen, while others wanted to share but not in a group setting. As Mary (Inuk) described, “It’s not always easy to say what you need to say in front of all these groups. It would be good to talk to someone one-on-one sometimes…for the really private parts of what you need to say.” Notably, the one-on-one interviews that were part of this project provided the opportunity for women to share in a more private setting. The only one-to-one support provided by the prison is the pastoral services. There is a need for culturally appropriate one-to-one services as well as collective spaces in provincial prisons.

« It’s not always easy to say what you need to say in front of all these groups. It would be good to talk to someone one-on-one sometimes…for the really private parts of what you need to say »

The women in the prison described culturally specific programs, such as the medicine pouch workshop, as a space to release emotions. Recognizing and respecting the women’s experiences of trauma and mistrust, the workshops were deliberately included in the project to provide an opportunity for women to engage in processes of establishing connection and a certain level of trust (McGregor, 2018). The medicine pouch workshops ran for three consecutive days, unlike any culturally based initiatives available at the time, giving women time to build relationships and trust amongst each other as well as with the facilitators. In this space, they were able to discuss the symptoms of their trauma (such as addiction, fighting etc.) and the roots of the trauma (colonial harm, intergenerational trauma, and systemic racism). Mainstream programs such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) did not address colonization as the root of harm, focusing solely on the symptom (i.e., alcohol). Culturally specific programs also allowed Indigenous women to connect with others who shared experiences of colonial harm, oppression, intergenerational trauma, and systemic racism. This allowed for connection and collective healing as they shared similar, although not the same, histories and worldviews. Providing enough time to build trusting relationships and give space to discussing the roots of issues is an important consideration to support Indigenous women’s healing.

Wanda, a Mohawk facilitator and Elder working in the community, shares the benefits of spaces for Indigenous women to come together in relationship and support collective healing:

Jissika (Inuk) describes how connecting with others in prison helped her feel less alone: “Sharing and listening to others. About how you feel…how they feel like how I feel…seeing myself that I am not alone.” The women also shared the benefits of having spaces just for them:

Michelle (prison staff) described the importance of community for Indigenous women: “Being in relationship with others, in the community, or in communities, within her social circle, so they can be involved and also to bring about change.” Rebecca (prison staff) also recognised the need for community and a sense of belonging amongst Indigenous communities in the prison:

« If there could be a unit where all the women could be together and go to work together. You know, create opportunities for Indigenous peoples »

Prison staff were also aware of the importance of building relationships and trust with Indigenous women. Vanessa shared the challenge of writing an evaluation in 62 days, which is the standard timeline. She shared that this is not enough time to build a relationship, particularly with Indigenous women who often take time before they feel comfortable sharing:

Vanessa also described the need for more time for evaluation and more consistency in following up with individuals. Another member of prison staff, Julie, talked about the need for relational repair and for support workers to build trust with Indigenous communities in order to regain their confidence. Some prison staff recognised that colonization, residential schools, and DYP impacts the women’s ability to trust them and the prison system. Jessica, who works in the community, highlighted how prison staff do build relationships with the women over time, however power dynamics exist between the women and staff that can lead to mistreatment: “In my experience working with prison guards, talking to prison guards, their view of things - they're bullies, but it's not the same way as police. Some of them, they actually build a relationship with the people.” Furthermore, having Indigenous support workers that the women can access helps to build trust as they feel represented. This sentiment was echoed by Emma, a woman in the provincial prison who is Inuk, “It’s really hard to trust, to find someone I can trust. For me, I feel better when I see people, Inuit people. They support each other a lot. Makes me feel better.”

« It’s really hard to trust, to find someone I can trust. For me, I feel better when I see people, Inuit people »

Continuity of care was also highlighted by the prison staff and community workers. Vanessa (prison staff) disclosed how staff turnover disrupts the progress made as it means having to re-build the relationships from scratch. Furthermore, she highlighted a need for more partnerships with community organization and supervision of the full process so that the women are accompanied and experience continuity of care during their re-entry process. One of the women, Maggie (Inuk), illustrated this:

« The one person that I have [was] the social worker. She was a really big help. She even came to my Portage [rehabilitation centre] graduation. It was a big thing. It was touching and was so helpful...and now she's gone and I have to start from zero »

This sentiment is echoed by community workers who shared success stories of healing and rehabilitation as those whereby the women were offered flexible and continuous support, that involves forming positive relationships with community workers and others in their community. They highlighted the success of continuous care throughout the women’s lives as they navigated the systems, and the role of trust and relationships in doing so. Serge (community worker) discussed the importance of stability and continuity:

Sonya (Inuk/French-Canadian), who works in the community, identified the need for services to stay connected and committed to Indigenous women and the community in order to be able to find them and help them navigate the legal systems:

Jessica, a community worker, shared the potential for healing through relationships and community:

« I think it can be very powerful that there's a whole community that doesn't label them as criminals…that a whole community is behind them - it can be very empowering for them to also sometimes reach out for help afterwards »

Elizabeth, who is Inuk and attended the workshops in the provincial prison, shared the impact of having access to culturally specific programs as it was a space to connect with others, open up, and feel less alone:

Luci, who works in the community, stated, “You have to be careful what you say, but you have to be a good listener as well. Listening is a big factor. Listening to the silences, too. If you don't listen, they won't talk.” Serge (community worker) described his experience and the ways in which the women might test the waters for the safety and trust of the group or support workers.

« you have to be a good listener as well. Listening is a big factor. Listening to the silences, too. If you don't listen, they won't talk »

Vicky (Cree/Métis community worker) also highlighted the power of listening: “Sometimes it's saying nothing at all. It's just holding that space, allowing the women to share what it is they need to share and without reaction, without turning things into drama, without questioning them or pushing them.” Finally, Serge also emphasized the importance of learning in order to best support Indigenous women:

« Sometimes it's saying nothing at all. It's just holding that space, allowing the women to share what it is they need to share »

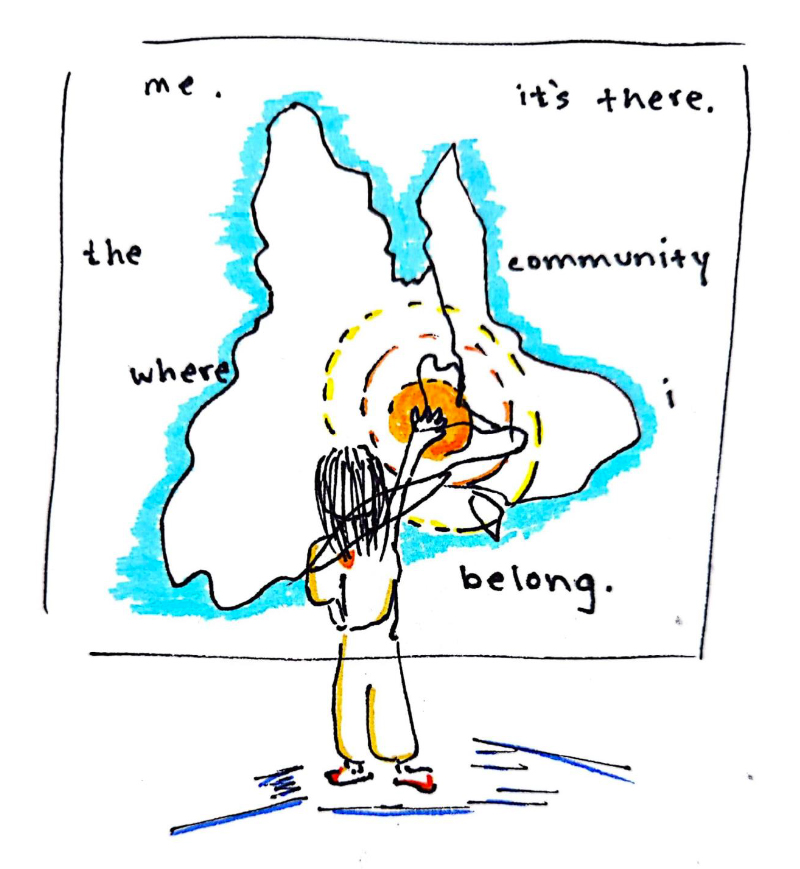

As an art therapist working in a provincial prison, I try to find ways to connect to the Indigenous women that I support. In my office, I have a big map of Quebec. It just sits there on the wall as the women visit me. I do not point it out or ask them to share anything. Yet, often, women will begin to interact with the map. As they talk about their homes and their communities, they point it out to me on the map. They will sometimes also make connections to other Indigenous communities on the map who are also represented in the prison. It was not my original intent, but the map is a tool for women to see themselves in my office and to share parts of them with me, as they see fit. One Indigenous woman pointed to the map and said, “Me. It’s there. The community where I belong.”

9This story was adapted from an interview with one of the community workers. The drawing was created by Rowena Tam.

The pervasive impact of colonization and colonial harm perpetuated by the current justice system was evident in this project. In order to develop services that support Indigenous healing, the current systems must consider Indigenous women’s complex life histories, cultural identities, and needs. We must integrate alternative approaches to healing and rehabilitation into the current criminal justice system and extend agency and autonomy for Indigenous women, who are or have been incarcerated, to make informed choices about the type of support that they want.

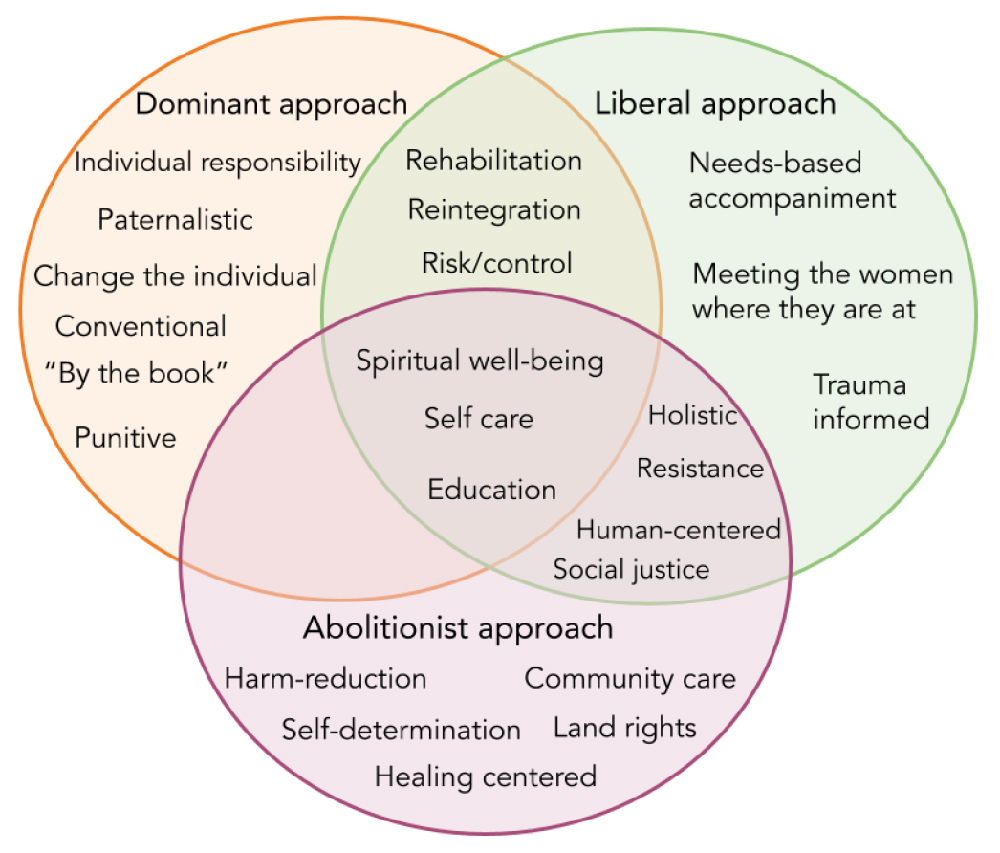

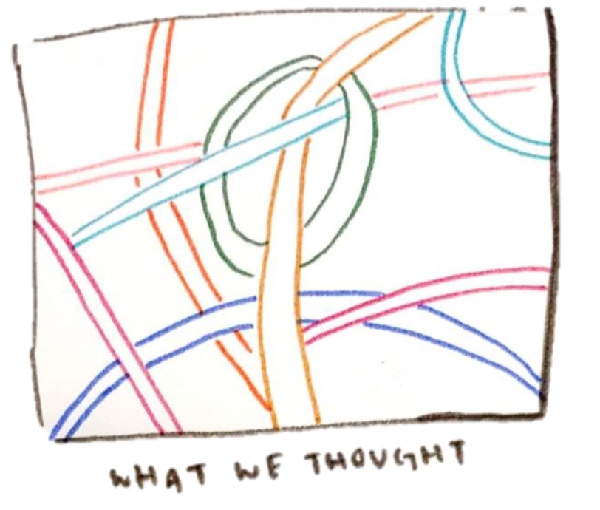

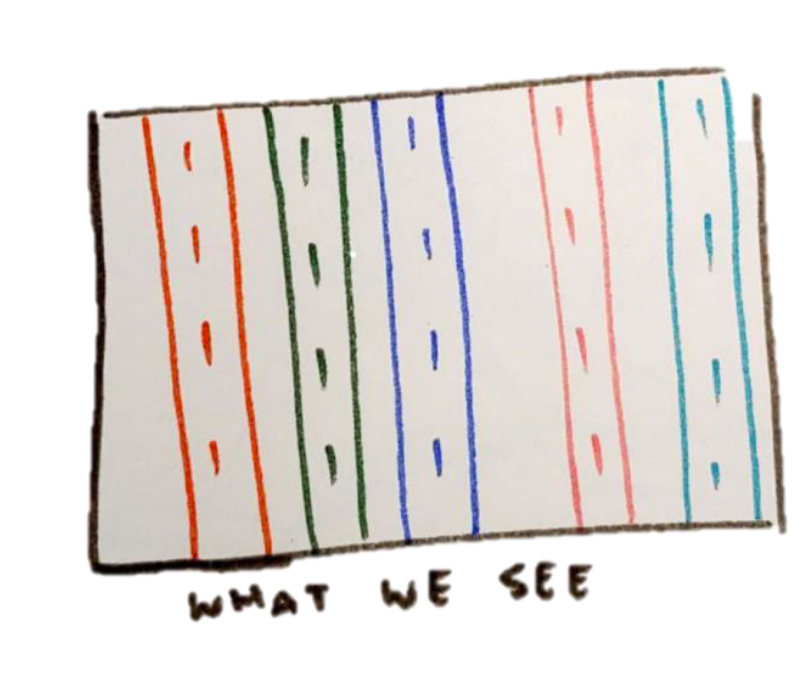

This section will discuss the different approaches to healing and rehabilitation identified in the study. First, the dominant approach, which largely governs the current justice system and offers a standardized and punitive method. Secondly, the liberal approach, which considers and attends to the individual needs of Indigenous women. Thirdly, an abolitionist approach, which calls for a new system that considers restoration, transformation, and harm reduction. Notably, these approaches are not mutually exclusive, and overlap can occur10. This section also reflects on the impacts of the current system on individuals working within it and calls for more collaboration and partnerships in order to attend to the current systemic failings of the support provided to Indigenous women in the criminal justice system.

As you read through, we invite you to consider:

10The Venn diagram illustrates the interconnectivity between these approaches.

The dominant approach considers how to support rehabilitation and re-integration for Indigenous women in prisons in a linear and binary process. Many prison staff asserted that the women must demonstrate a willingness to change in order for rehabilitation to be successful. Some community workers also leaned towards the work philosophy of rehabilitation that centres the need to become a “productive member of society” and takes on a more concrete approach to reaching specific goals that are articulated externally. For example, sobriety as a condition for continued support. Liane, who is opening a transition house for women coming out of rehab, describes the conditions and the benefits of a rehabilitation structure: “So, that means staying sober and finding a career, finding self-sufficiency, becoming independent. It's not the same as healing, but it just definitely needs to be a part of their plan.” This approach was also taken in AA offered in the prison and some organizations that support women with re-integration.

The dominant approach uses a top-down and corrective approach to rehabilitation that offers specific rules and conditions whilst putting the responsibility on the individual to change. This approach also focuses on the symptoms of the problems, such as alcohol, addictions, and violence, without much consideration for the root causes. Mathieu (prison staff) described rehabilitation as the “power of the woman, with support, to stop behaviors and attitudes that are counter-productive [and] against personal growth.” Rachel, who works in the community, shared what rehabilitation aims for: “You can find a job. You can fit into society. Like, it's a lot about capitalism and that kind of thing.” Serge (community worker) also discussed the ways in which the criminal justice system prioritises security and the challenges this poses to support healing and rehabilitation:

« The number one priority is security, and that poses a major challenge to be able to provide a therapeutic environment that will foster rehabilitation »

This approach expects Indigenous women’s needs to fit into a system that was not designed with them in mind. Others have noted that the correctional system uses standardized tests, procedures, and policies that are culturally inappropriate and largely developed for men by men (Monture-Angus, 2000). Prison staff shared the challenges of applying the dominant processes to Indigenous women. Cristine, who works in the prison, described how it was not realistic for Indigenous women to be able to follow the conditions that the prison imposes on them:

« we have not yet learned to adapt our idea of White justice »